Updated February 25, 2024

Contents

A familiar mystery

An impossible quest which succeeded

What pitches shall we select to play music?

A rule both empirical and mathematical

The natural scale

A problem without a solution

Are the friends of my friends my friends?

Unperfect yet practicable solutions

The equal temperament from a mathematical standpoint

Traditional keyboard vs uniform keyboard

Small hands are fine

Tradition doesn’t mean you are right

Other clever keyboards

Great, but they are not pianos any more...

Symmetry: another idea on which to elaborate

For more information

If you (want to) play guitar

The Bilinear Uniform Chromatic Keyboard (BUCK)

A familiar mystery

The series of black and white keys on a piano, organ or synthesizer keyboard is among the most familiar patterns to everyone, not only musicians.

Did you ever wonder why are the keys arranged this way and why the regularity is sometimes broken, each time to the advantage of the white keys?

An impossible quest which succeeded

If you have some knowledge about musical notation or music history, you may know that the choice of intervals (difference of pitch between notes) that is almost ubiquitous on today's keyboard instruments and on most other instruments was not made in a day. This choice is called a "temperament", and in western music, a wide agreement has been reached more than a century ago on the so called "equal" temperament.

To bridge a given pitch (or frequency) to a pitch twice as high (known as the octave) in equal temperament:

- twelve intermediary steps called semi-tones are used;

- the pitch ratio (i.e. frequency ratio) between a note and its upper neighbour (either black or white key) on the keyboard is always equal to a semi-tone.

What pitches shall we select to play music?

Now that we have an idea of the solution, let's see what the problem was. Basically, the challenge is the following: how can we get from a sound with a given pitch to the sound whose pitch is twice higher, using in between a number of levels that may be combined at will ? This "one to two" ratio is extremely important, because two sounds whose frequencies are in such a relation give a feeling of perfect agreement. You would almost say that it is the same sound, that we are "back home", except, of course, for the fact that the sound with double frequency is very significantly higher pitched than the original sound. We’ll see later on why this untouchable interval is called "octave"

It is at first sight straightforward to split the octave interval into as many levels as we want, with arbitrary pitches lying between the original sound (say frequency F) and the sound at the octave (doubled frequency, 2F). However, if we want to have an impression of harmony in hearing those sounds, as opposed to a more or less arbitrary cacophony, we must ensure that this division complies with rules which are based on mathematics and physics, but nonetheless reflect our feeling of the consonance and aesthetics of a set of sounds.

A rule both empirical and mathematical

This rule states that the levels to be chosen while dividing the octave must match simple frequency ratios. For instance, if we experiment with a guitar string, the frequency ratios are exactly the reverse of the string length ratios (string tension remaining equal). So if we press the middle of a string against a fret, we divide the length of the string by two and so we get a sound whose pitch is twice as high. If we press on the seventh fret, the vibrating section of the string has a length which is 2/3 of the overall string, and therefore vibrates at a frequency 3/2 F, that is one and a half times the pitch of the original sound. This is the interval of fifth, the most important one after the octave. The sounds whose pitches have simple ratios like the octave, the fifth and a few others are the one we consider harmonious or "consonant". We would then like to select among those sounds a set of levels that would allow us to travel in the world of sound relations and create in there paths which are "talking" to us.

The natural scale

There is some latitude in the choice of these levels, but for the present purpose we’ll just take the so-called "natural" major scale, which allows us to set milestones across the octave by using the following ratios to the fundamental (lowest note), here C:

| fundamental | major second | major third | fourth | fifth | sixth | major seventh | octave |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C |

| 1 | 9/8 | 5/4 | 4/3 | 3/2 | 5/3 | 15/8 | 2 |

There exists also a minor scale, which uses slightly different ratios.

A problem without a solution

Once defined this natural scale, a major difficulty soon appears: the pitches set this way are perfectly accurate relative to the fundamental (here C), but they are much less so when the various degrees are considered relative to one another. For instance, G in the natural scale above is defined as a perfect fifth relative to the initial C (frequency ratio 3/2), and similarly A is a perfect sixth relative to this C. However, the interval between G and A is (5/3) / (3/2) = 10/9. This is less than the chosen value for the major second (9/8 between C and D). If we go beyond the octave of C, the pitch ratios get more and more wrong (drift).

This problem has no perfect solution.

Are the friends of my friends my friends?

To give an image, we could say that the "ideal friends" of a sound aren’t ideal friends to each other. They remain somehow friends to each other, but the harmony between them is not as perfect as with their common friend. If we take a chain whose adjacent neighbours are always "ideal friends", the ends of the chain might well be no friends at all!

Unperfect yet practicable solutions

For instance, if twelve successive ascending natural fifths are played, the next to last note, though approximately one fifth below the seventh octave of the starting note, will sound quite dissonant to it ("wolf’s fifth").

Numerous approximate solutions to this problem were proposed for practical use in the course of centuries. One could for instance try to make all the fifths a bit lower (and then slightly wrong) in order to get back on one’s feet at the seventh octave. The solution which is almost universally adopted nowadays for that class of problems is the perfectly regular division the octave called equal temperament.

The equal temperament from a mathematical standpoint

To understand what the equal temperament is, we'll need a touch of maths. In the equal temperament, the (major) second, that is the full tone, e.g. C to D, has a value of the sixth root of 2. This number, which is not at all a simple ratio anymore, but on the contrary an irrational number, has the remarkable property of yielding 2 when multiplied six times by itself. Translating in terms of sounds, this means that by concatenating six times this one tone interval, we quite accurately reach the octave of the original sound. There is no more drift when reaching another octave by stacking smaller intervals. All the intervals, except the octave, are very slightly inaccurate, but:

- The over important fifth remains almost perfect;

- To most listeners, other gaps are well below their perceptive capabilities;

- We no more have strong dissonances.

Moreover, the ear is largely forgiving to homogeneously distributed small gaps in pitch. The semi-tone interval, which is the smallest interval we can get on a fixed-tone keyboard instrument, is exactly the half a full tone, and its value is therefore the twelfth root of 2.

Now that it is perfectly clear that almost all classical, jazz, rock, etc. uses a uniform division of the octave, we can get back to the original question: why are the piano keyboard keys laid out in an irregular fashion?

Traditional keyboard vs uniform keyboard

To answer this question, we will present a keyboard type which produces exactly the same pitches (those peculiar to equal temperament, based as we just saw on this very peculiar number, the twelfth root of two) than the traditional keyboard, but whose key layout reflects the regularity of the pitch sampling.

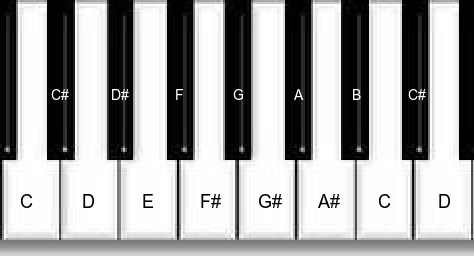

We’ll call this keyboard Bilinear Uniform Chromatic Keyboard (BUCK for short). You may also see it called e. g. "6-6 keyboard", "balanced keyboard", "symmetric keyboard" or "uniform keyboard system". You can see below the difference between the standard keyboard (left) and the bilinear uniform chromatic (right):

|

|

Now let's take a look at the chart below, comparing the features of the traditional keyboard with those of the bilinear uniform chromatic keyboard (BUCK).

For every octave in the traditional keyboard, we have 7 long and wide keys, usually white, and 5 short and narrow keys, raised above the white keys and usually black. The BUCK however displays 6 long keys and 6 short keys.

| Traditional keyboard | Bilinear uniform chromatic keyboard (BUCK) |

|---|---|

| Using only the white keys, the beginner has straightforward access to a diatonic instrument, allowing him to play simple melodies and chords in C major. | No scale is put forward. The instrument is chromatic by its capabilities as well as by its interface. However, a key coloration can be adopted, corresponding to the traditional keyboard, with white keys for C major. |

| The student must learn 24 scales to play everything, minor and major. | The student must learn 4 scales (two pairs of symmetrical fingerings) for the same result. |

| Depending on their positions, identical intervals require different spans between the fingers. |

A given span of the fingers will always produce the same interval (third, fifth etc.), whose amplitude is always proportional to the span. Moreover, the finger stretch required by a given interval will always be smaller or equal to what is required by the traditional keyboard for the same interval. |

The first point is an incontestable strength of the standard keyboard. Notice however that most beginners still look at their keyboard while playing, so the color of the keys still allows them to play in C major on the BUCK.

For the sake or aesthetics as well as for training the sense of touch right from the start, one might prefer to mark C and C# with small spikes, like on the G and H keys of computer keyboards.

The second point (six time less scales to learn) is probably enough to reduce the length of the technical piano training by a factor 2 at least.

Small hands are fine

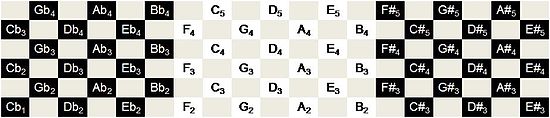

Now let's take a closer look at the third point :

L = half width of a low key (usually white)

| Interval | Traditional keyboard | BUCK |

|---|---|---|

| minor second (½ tone) | L (e.g. C to C#) or 2L (e.g. E to F) | L |

| major second (1 tone) | 2L (e.g. C to D) or 3L (e.g. E to F#) | 2L |

| minor third (1 ½ tone) | 3L or 4L | 3L |

| major third (2 tones) | 4L or 5L | 4L |

| fourth (2 ½ tones) | 5L or 6L | 5L |

| diminished fifth (3 tones) | 6L or 7L or 8L | 6L |

| fifth (3 ½ tones) | 8L or 9L | 7L |

| augmented fifth (4 tones) | 9L or 10L | 8L |

| sixth (4 ½ tones) | 10L or 11L | 9L |

| seventh (5 tones) | 11L or 12L | 10L |

| major seventh (5 ½ tones) | 12L or 13L | 11L |

| octave (6 tones) | 14L | 12L |

We see that the BUCK is less penalizing to small hands. A hand with a span of 16L (eight times the width of a white key) won't always be able to play a ninth on the traditional keyboard, but it will always be able to play a tenth with the BUCK.

Tradition doesn’t mean you are right

We'd like to stress the advantage of having intervals always proportional to the fingers' gap, because it makes approaching a keyboard so much more intuitive and natural.

This significantly facilitates acquisition of automatisms. Notice incidentally that the dissonant and dreaded tritone (diminished fifth) is particularly welcome by the traditional keyboard, which offers 3 possibilities to produce it!

Other clever keyboards

In the family of uniform keyboards, different layouts exist. Most of them do not settle for the two rows of keys featured by the BUCK, but added several rows of keys or buttons. The basic principle was invented during the nineteenth century. Though some non-laymen like Franz Liszt considered this was the ineluctable future of the instrument, the uniform keyboard layout remains today extremely confidential, except maybe for some accordions. Uniform MIDI keyboards (but not bilinear) have been briefly available on the market, but weren't successful. In order to have a MIDI keyboard with this key layout, you will then have to be a talented hobbyist (see [17]), or have it made by a craftsman (see also [6]). Lobbying electronic instruments manufacturers could also be considered.

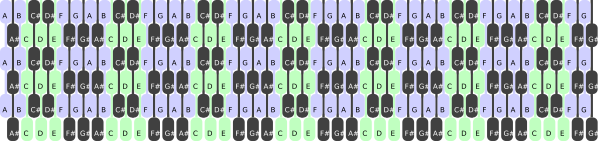

Among them are the Janko and Wicki keyboards, which are elaborations of the bilinear uniform concept. They do provide additional benefits relative to the BUCK presented above:

- only 2 scales must be learned, instead of 4 scales (two by two symmetrical) in the case of the BUCK

- intervals significantly wider than the octave can easily be achieved.

Janko keyboard layout

|

|

Layout of Wicki keyboard (Wikimedia Commons image)

Great, but they are not pianos any more...

My personal point of view is that in this case the best is the enemy of good:- the postures are not uniform any more since the hands must move in the direction perpendicular to the keyboard to reach for keys laid out along both directions;

- the keys are not traditional piano keys but rather buttons, which implies much difference in attach and touch, and probably make dynamic rendering more difficult;

- the same note can be obtained through two or three different keys, the same chord at several different places, hence eventual hesitations compromising the acquisition of automatisms;

- the keyboard does not look like a piano keyboard anymore but instead presents a weird aspect.

First, the technical sophistications brought into non electronic piano making might not always be applicable to instruments featuring several rows of keys.

Then the two first points risk rendering inapplicable part of the traditional piano playing technique, which in the case of the BUCK is solely retained and simplified.

Whatever the interest they present, those instruments don’t offer much of the sensation and ergonomics associated with the traditional piano, whose familiarity inspires both sympathy and fascination.

I think that, together with the unavoidable inertia, the above was quite enough to relegate those remarkable keyboards to a statute of mere curiosity, and by the same token make forget the simpler and more intuitive BUCK.

The commercial failures of the Chromatone [15], marketed a few years ago, of the Axis 49/64 [20] (store closed in February 2015) and of a few others only seems to confirm that opinion.

Chromatone keyboard (marketed in 2005, unavailable today)

Axis 64 keyboard (store closed in 2015)

Here is the Terpstra [21]. very sophisticated instrument designed among other things to facilitate the transition for traditional keyboard players. While it is not readily available, it is possible to pre-order it on the website.

Terpstra keyboard (pre-orders accepted on website)

Symmetry: another idea on which to elaborate

However, there does exist a keyboard concept that goes beyond the simple bilinear keyboard presented above while remaining a piano keyboard, which means that it features standard piano keys, as opposed to buttons and additional rows. It is based on the simple observation that our hands are symmetrical and not identical, though neither the traditional piano keyboard nor the basic bilinear layout take this primordial fact into account. So usually, when you play a chord with the right hand, the bass is played by the thumb, while if you play the same chord with the left hand, on the contrary, the thumb will play the highest note. With the different muscular efforts required from each finger, memorizing the fingering and the dynamics of a chord position is then quite different whether you hold it with the left hand or the right hand. It will take more effort to assimilate and more resources to be stored in the brain. With the symmetrical version of the Uniform Keyboard System [11], on the contrary, bass notes are played nearer from the body, and higher notes further away from the body, i.e. by stretching the arms, both for the right and the left hand! Note that this site also offers a simple and clear PowerPoint presentation.

To fully exploit this idea of symmetry, one could imagine a layout in two separate parts in the shape of circle arcs, one for the left hand and one for the right hand. The two keyboards would be more or less mirror images of each other, with some redundancy between the two parts to avoid jumps. This idea of symmetry is obviously less convincing in the case of a traditional monolithic keyboard, but nothing prevents you from trying such a tuning if your MIDI device allows it.

While not a tabular keyboard, the Dualo [12] appears to be an extremely interesting device regarding both the uniformity and the symmetry between hands. It is a portable instrument, reminding a bit of an accordion, and having the tremendous advantage of being commercially distributed and available TODAY (February 2015). However, you can’t reprogram the keys and the symmetry of hand motions does not seem to be leveraged on the current Dualo.

Dualo instrument, currently available (as of February 2015)

Besides entering a shop to try the Dualo (in France, see the list on the website), you also have the possibility to get acquainted with uniform keyboards by downloading to your Android tablet the Hexiano app. Of course a touch screen will never be a genuine keyboard, yet this application is very well designed, with e.g. adjustable (hexagonal) key dimensions and three options for the layout: Janko, harmonic table (like the Axis models) or Wicki-Hayden (like the Jammer/Thummer models).

Future successes or definitive failures, those projects among many others irrevocably demonstrate that the traditional keyboard, whose fundamental structure is wonderful, but whose key layout shortcomings translate in the best case into tremendous learning time losses, and in the worst (and most frequent) case in complete desertion of musical practice, can nowadays only be justified by habits and conformism. One might also wonder about the extent to which the decline of classical music is related to the huge (yet mainly unnecessary) difficulties associated with the learning of the piano, which is still, with its absurd layout, the main instrument used for composing.

For more information

- For more information on the musical keyboard and its origins, refer to [1].

- For a simple presentation of the uniform keyboards and Janko keyboard, see [2], [8].

- For interesting debates and links to alternative musical keyboards, see [3], [4], [9], [10], [13], [14], [15], [18].

- Excellent site with intuitive instrument making improvising easier [5].

- Paul Vandervoort’s site with maybe MIDI Janko style keyboards available.[6].

- Paul Panebianco’s site, with other interesting links.[7].

- José Sotorrio’s site with a nice presentation and many keyboard images (look in the photo section).[16].

- Bart Willemse’s balanced keyboard website with instructions on how to build your own balanced keyboard (aka bilinear uniform chromatic keyboard) from a synthesizer with a standard layout.[17].

- Dominique Waller’s website about the symmetrical keyboard (« clavier symétrique », still another term referring to the same uniform keyboard) with incredible stories from distant or recent past as well as an extensive list of links and videos.[22].

- This nice video will show you a BUCK in action.[19].

If you (want to) play guitar

If you play guitar and once tried to tune your guitar major thirds, you know the wonderful feeling to play a uniform instrument. Otherwise, just take a look on my page Major thirds: a new tuning that changes everything and experiment !

Add your commentLinks

- [1] Musical keyboard - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- [2] The Uniform Keyboard

- [3] The Organ Forum - Interesting Keyboard Arrangements - anyone tried one?

- [4] Kill me, but it would be a breakthrough!?

- [5] Alternative Musical Instruments

- [6] Daskin Uniform Keyboard Musical Instrument Systems

- [7] Of Interest - Alternate Keyboard instruments

- [8] Sequence 15: Alternative Keyboards (en anglais)

- [9] Janko Keyboard - Piano World Piano & Digital Piano Forums

- [10] Daskin! - MusicPlayer Forums

- [11] Video demo of the "Uniform Keyboard System" by Joseph Saltsmann

- [12] The Dualo principle

- [13] Another Bizarre Music Keyboard: Riday T-91

- [14] New Ways of Playing Keyboards: Samchillian and Thummer Redux

- [15] Chromatone 312 Key Synth Laughs in the Face of 88 Keys

- [16] José Sotorrio’s Bilinear Chromatic Keyboard

- [17] Bart Willemse’s balanced keyboard website

- [22] Dominique Waller’s website about the symmetrical keyboard, also in English

- [18] Sound On Sound Forum: Music Theory, Songwriting & Composition

- [19] Ruby my dear, played on a symmetrical keyboard - YouTube

- [20] C-Thru Axis 49 & Axis 64

- [21] The Terpstra Keyboard Concept - 280 Color Changing Continuous Controllers